A Moment In History: The Civil War Years of the Allegheny Arsenal

By James Wudarczyk

Although the Allegheny Arsenal played a key role in American and Pittsburgh history, it has been shamefully overlooked and remains today a neglected landmark. The stone walls and four Civil War remaining structures are the sole surviving silent sentinels of the turbulent period between 1861 and 1865.

During the 1930s Charles Morse Stotz, a prominent Pittsburgh architect, was among the earliest persons to recognize the architectural and historical importance that the Allegheny Arsenal played as a military facility. Commissioned by the Roosevelt's Works Public Administration, Stotz drew a number of detailed drawings and photographed the pre-1860 buildings that remained on the grounds of the former Allegheny Arsenal. In 1936 the Buhl foundation provided a grant for the publication of his book The Early Architecture of Western Pennsylvania. This work was reproduced by the University of Pittsburgh in 1966 and again in 1995. Stotz wrote, "The Arsenal was an active government post until 1926, when it was sold at public auction. Since that time many of its buildings have been drastically altered, and a number of large shops and warehouses have been erected. But enough remains for one to visualize the one-time impressiveness of the whole."

It is ironic what a difference of thirty years made in the life of the Allegheny Arsenal. In 1967 James D. Van Trump and Arthur P. Ziegler, Jr., in their monumental Landmark Architecture of Allegheny County Pennsylvania, wrote, "This is merely a contemporary record of remaining fragments. It would seem that the Arsenal is probably beyond restoration even if some omnipotent Maecenas or official agency would attempt it, but the area does need more study as one of Pittsburgh's important early architectural landmarks."

One must agree with Van Trump and Ziegler's assessment that a recreating of the Allegheny Arsenal in its heyday would be impossible to reconstruct.

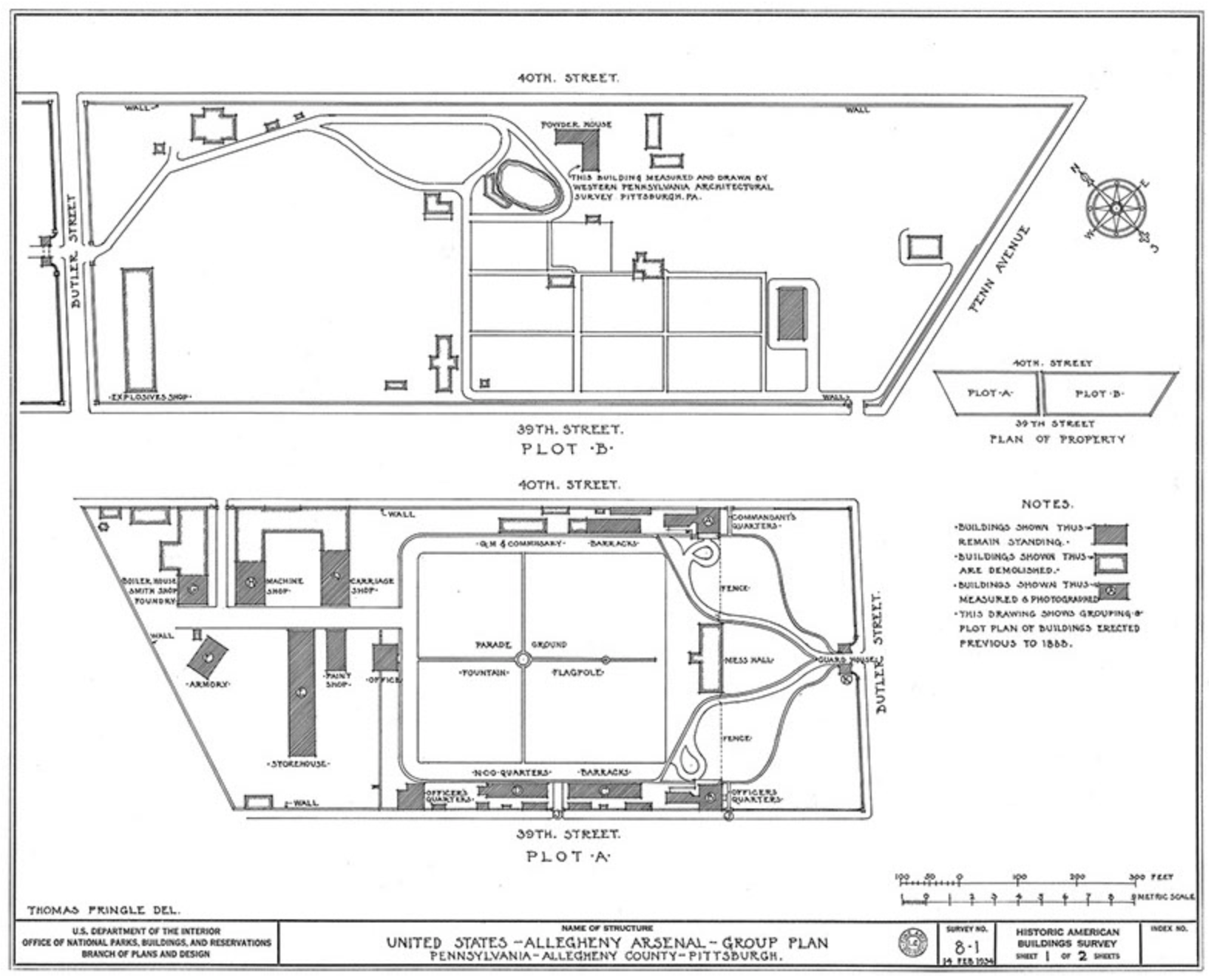

The earliest known description of the facilities is found in the May 1835 issue of The Military and Naval Magazine of the United States. This account was among the earliest to refer to the military reservation near Pittsburgh as the Allegheny Arsenal. The account was later reproduced in Israel Rupp's 1846 Early History of Western Pennsylvania. These works noted that Butler Street divided the Arsenal into two parts, with the upper park containing brick stables, three small frame buildings, and a powder magazine with storage capacity for 1300 barrels. The lower park was the heart of the arsenal with a three stories high stone military store, two carriage and three timber sheds, the main arsenal or magazine of arms, a three stories high building with a tower that was forty feet square at the base and 120 feet high, officer's quarters, barracks, armory, smithy, carriage shop, machine shop, paint shop and accoutrement shop. Total cost of the construction of the Arsenal was $300,000, a phenomenal sum for the period.

The Allegheny Arsenal found itself propelled into the major news events of its day when on December 23, 1860 Major John Symington received a controversial order from Secretary of War John B. Floyd to ship one hundred twenty-pound guns to New Orleans. To further add to the controversy, the cannons were to be shipped from the arsenal to two gulf forts under construction and not equipped to mount armaments. The orders No. 666 and 667 for Christmas Eve 1860 included 21 10-inch Columbiads, 21 8-inch Columbiads, and four 32-pounder guns for Lt. E. F. Prime, at Ship Island, Biloxi, Mississippi, and 23 10-inch Columbiads, 48 8-inch Columbiads, and seven 32 pounder cannons for Lt. W. H. Stevens, at Galveston Harbor, Texas.

Major John Symington apparently received the order for supplies on December 22, 1860, since that is also the date that Symington had recorded in the 1860 - 1861 Orders for Supplies logbook. A notation also indicated that the orders were filled or "issued" on December 24, 1860.

The fact that Captain William Maynadier's name appeared on the orders led some to theorize that it was Maynadier, and not Floyd, who was ultimately responsible for starting the crisis. One problem with this theory is that Maynadier did not have a motive for wanting the armament to fall into the hands of the fledgling Confederacy.

However, because of his role in the transfer of the cannon, he was charged in 1862 with disloyalty as an accessory to John B. Floyd in the alleged attempt to transfer arms, artillery and munitions to the South. The investigating committee acquitted Maynadier on all charges.

The angry mood of the people of the city was probably reflected best by the Pittsburgh Gazette, which wrote on December 25, 1860: "These facts go to show conclusively the treasonable purpose of the administration. Every Northern Arsenal has been stripped of arms and ordnance, and every Southern Arsenal crammed full and left in such condition as to give the Secessionists a chance to capture them, and provide themselves thoroughly with the accoutrements of war, at the expense of the government... The traitors of the South are thus being furnished by a government in league with them with all the ammunitions of war."

At a mass meeting in the Court House, it was decided that the president and other government officials should be alerted to the crisis in Pittsburgh.

When the president learned of the orders to ship cannon and other arms from the Pittsburgh arsenal, he apparently felt that two scandals involving Floyd was more than could be tolerated. (The other scandal involved his apparent knowledge of misappropriating bonds held in trust for the American Indian). Buchanan did not have the heart to fire the Secretary of War, especially on Christmas Day. Working through other cabinet members, James Buchanan thought it best to persuade Floyd to resign his position as Secretary of War. Floyd had been ill for some weeks, and these events pressed very heavily on his emotional health.

When Floyd learned that it was the president, who personally ordered the countermanding of his order to remove guns from the Allegheny Arsenal, he flew into a rage because he believed that Buchanan had undermined the authority of his position.

The next day, Floyd - although uninvited - attended a cabinet meeting where he was hostile and spoke very discourteously to President Buchanan. These sharp differences with the cabinet afforded John Floyd the excuse he needed to resign his position.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War, the Allegheny Arsenal was under pressure to increase production, and there were occasions where problems arose. On one occasion, Captain Charles Kingsbury of the Ordnance Department criticized Colonel John Symington, commander of the Allegheny Arsenal, for not providing proper articles for field carriages to Captain Howe and General McClellan. In a letter of June 12, 1861, Symington fired a sharp letter to Kingsbury in which he argued that the equipment matched the requisition and was in accordance with the Ordnance Department manual.

The problem of supplying the troops with arms and other equipment was an on-going affair. Symington's letter of October 2, 1861 to General Ripley in Washington, D.C., the commander had to give a detailed explanation for the reason that the facility was lagging in meeting expected quotas. He wrote, "I regret at this time when it is so important to push forward the laboratory operations, to have to inform you of a delay in them arising from too serious a cause to admit of being postponed. Some weeks since, matches were discovered among the bundles of cartridges prepared to be packed, in one of the rooms. The strictest investigation failed to detect the offender. Stringent measures were then resorted to and the boys searched on going to work, and leaving, which still continues. The offense has, however, since repeated in the same room. And as the perpetuators could not be discovered, all the boys employed in the room, over twenty in number, were on each occasion, discharged, and have not been re-employed. It was hoped, as some two weeks passed since the last occurrence, that the malicious spirit has quelled, but yesterday, a similar attempt at mischief was discovered in the same room. That the offender did not belong to the room, is thus made evident and I have discharged all the boys at work in that portion of the laboratory, and will supply their places with females. This must produce some delay but I am assured from the number of applicants for that kind of work, it will only continue for two or three days while they are acquiring the requisite skill."

While Symington was active in keeping up the Lawrenceville arsenal both prior to and during the Civil War, he was not popular in the neighborhood as an article from The Daily Pittsburgh Gazette of October 3, 1861, indicated:

"Considerable excitement existed in Lawrenceville during Wednesday, in consequence of the discharge of two hundred boys in the United States Arsenal in making cartridges, etc. It would appear that during the past few months, matches have been found no less than three times, in rooms where these boys were employed, and extravagant rumors have been circulated in regard to attempts to blow up the magazine, etc. Some of the people residing near the Arsenal were so apprehensive, under the excitement of these rumors, that they feared to lie down at night, lest they be blown to fragments before morning. The first and second scare passed off without any other notice than the gossip of the village and a 'sensation' item in one of the newspapers. The third discovery of matches, however, if we are correctly informed, has induced the commander of the Arsenal, Major Symington to discharge all of the boys heretofore employed in the place, numbering about two hundred. As the work at which these lads were engaged is indispensable under existing conditions, their places are being filled by girls as rapidly as possible. What benefit is likely to result from this change we are at a loss to determine, and there are persons at the village who pronounce the act a wanton display of arbitrary power. So many boys, thrown out of work at the approach of winter, must cause no little provocation, although it will be a measure lessened by the opportunity afforded to the girls, however questionable the change may be in a moral and social point of view."

In volume one of his monumental study of the Ordnance Department, Dean Thomas resurrected two incidents of poor quality at the Allegheny Arsenal. However, he notes that inferior quality was an exception to the rule, and as the text noted, sometimes there was an explanation for the complaint. When Lieutenant Colonel G. D. Ramsay, the commander of the Washington Arsenal, complained that the ball of the Enfield cartridge received from Pittsburgh was too large, Symington responded, "... For the Enfield rifle a sample gun of inferior quality, was sent here from the State of Ohio, by which to make the cartridge."

On another occasion, in May of 1862, the 16th Ohio complained that "many of the Cartridges were entirely destitute of Powder and many others were only partially filled." Symington argued that state arsenals probably reused some of the cartridge boxes since pasteboard was not used for cartridge paper at the Allegheny Arsenal.

In 1862 the Allegheny Arsenal was the scene of the worst civilian disaster in the history of the American Civil War. On September 17, 1862, while the battlefield of Antietam was swallowing thousands of casualties from both side in the bloody conflict, three disastrous explosions ripped through one of the laboratories where cartridges were being loaded at the Lawrenceville facility. By the time the calamity was over, seventy-eight persons, mostly teenage girls, were dead.At the time of the tragic event, one hundred fifty-six persons were working in the laboratory and approximately eleven hundred were employed by the federal government at the Allegheny Arsenal, where they labored loading cartridges, repairing and manufacturing leather accoutrements, building gun carriages and caissons, loading artillery shells, and filling canisters with grapeshot.

There were two major investigations into the incident. The first was conducted by Coroner McClung, who impaneled a jury on the evening of Wednesday, September 17, 1862. The jury consisted of John W. Riddle, Lawrenceville; H. S. Donaldson, 4th Ward; J. B. Hill 9th Ward; F. C. Negley, 5th Ward; Henry Snowden, Lawrenceville; and John Lowe, 3rd Ward. At nine o'clock the following morning, the jury assembled in the Lawrenceville borough council chamber, where they began to take testimony. For the next several days, the Daily Post reported on the proceedings of the inquiry. At the conclusion of the inquest, the jury was divided and could not agree on a verdict. The majority of the jury resolved that they regarded the accumulation of vast quantities of gunpowder and other explosive materials in and near the United States magazine buildings, located in the borough of Lawrenceville, as a great public wrong, unwarranted by any exigency of the service and fraught with imminent peril to the whole community. Furthermore, the majority believed the explosion to be caused by neglect on the part of Colonel John Symington, Lieutenants J. R. Edie and Jasper Myers, and the gross neglect of Alexander McBride, Superintendent of the laboratory building and his assistant, James Thorp. The majority opinion was written by John McClung, H. S. Donaldson, John Lowe, F. C. Negley, and Henry Snowden.

John W. Riddle, foreman of the coroner's jury, and James B. Hill were of another opinion on the matter. They wrote, "From so much of the foregoing finding as imputes negligence to Colonel Symington and Lieutenants Myers and Edie, we utterly and entirely dissent. The testimony, in our judgment, clearly discloses that the sad disaster is to be attributed to a disregard by the Superintendents of the wholesome and stringent orders of Col. Symington, and we are unable to find anything in the evidence criminating either of his Lieutenants."

John Symington was livid when he heard the findings of the coroner's inquest. Since he was in the military, he did not have to cooperate with a civilian inquest. Being eager to discover the cause of the great tragedy, he willingly agreed to assist and made his staff available for the proceedings. Since he considered the findings unjustifiable, Symington called for a military inquest into the matter. The military inquest into the explosion was held in October 1862 and after extensive examination and testimony, the board ruled that Symington had not acted improperly and no blame for the disaster could be laid upon him. At the conclusion of the military inquest, the board determined that there was an explosion at the Allegheny Arsenal that resulted in the loss of life and property, and no cause could be determined as the sole reason for the disaster.

The cause of the explosion remains one of the great mysteries of history. Among the more bizarre theories contends that Confederate prisoners being used as laborers sabotaged the facility or youths were playing with fireworks. Although never proven or disproven, the most accepted theory is that a horse's hoof struck a hard stone that set off the deadly spark. However, if one was to look at isolated pieces of testimony from the coroner's inquest, it would be possible to build a number of scenarios. Perhaps it might be successfully argued that negligence on the part of the government, the workers, and Du Pont played some role in the deadly mishap.

Although the government posted safety rules, there is evidence that these standards were not adequately enforced. For example, Elias McClure stated that McBride preferred the powder that spilled on the floor to be gathered up but never enforced that rule. Also, Van Fowler testified that there were not enough moccasins in the laboratory for all of the boys and men working there.

Then one may impute the guilt of negligence on the part of the workers themselves. Knowing it was very dangerous to work with gunpowder, workers often showed little regard for the work rules, their own safety, and the welfare of their fellow workers. Gottleib Ryan, who was injured in the explosion, presented his testimony from his home. He contended that rules regarding loose powder were strictly enforced but boys between the ages of twelve and thirteen would often disobey the rules when their supervisors were not present. In spite of the danger of setting off gunpowder, Van Fowler admitted to having been reprimanded for wearing heavy shoes in the laboratory. Apparently he received multiple reprimands, because he testified the admonishments had not been in recent times. While Robert Dunlap's testimony was very critical of the safety precautions at the Arsenal, indicating to the jury that he was never requested to change his boots, which had two rows of heavy nails on the soles, it reinforces the theory that workers were equally negligent in adhering to safety procedures. Why would someone wear heavy boots with nails into a hazardous area?

From the testimony, it appeared that empty crates were not being removed from the laboratory often enough. As a result, barrels of musket powder may have been left on the porch of the building overnight. As a result of congested conditions, one may conjure a vision of Robert Smith - one of the fatalities - may have had to climb over barrels of gunpowder to reach the empty crates.

Although we will never know the reason for the explosion, the testimony of Alexander McBride that DuPont Company required the recycling of empty barrels may have validity as a key element in the tragedy. McBride could not understand why the gunpowder barrels were returned since the lids never fit as snug after they were pried open. This would have accounted for powder being shaken from the barrels in transit. Considering the fact that DuPont was the largest manufacturer of gunpowder in the Union, no further investigation was made into the matter. The military simply wanted to close the books on the great tragedy at the Allegheny Arsenal and resume wartime production.

Dean Thomas, in his monumental task of tracing the triumphs and failures of the arsenal system, quotes a letter from Major Robert H. K. Whiteley, dated February 23, 1863, "The capacity of two presses at this Arsenal is to produce 40,000 bullets per diem... which is about one-fourth of the quantity consumed daily." But he continued, "The manufacture of small arm cartridges must stop for want of storeroom shortly unless relieved by issue. I have eight million at this moment stored in a leaky frame shed, by no means safe from accident by fire."

During the election of 1864, the Allegheny Arsenal again worked its way into local newspapers when a number of employees were dismissed for their political views. While Lieutenant Colonel Whitely was on leave, Captain Harris and some of the supervisors made it known that any person who planned to vote for George McClellan instead of Abraham Lincoln for president was a traitor and would be subject to dismissal on the day after the election. Believing this was a form of political harassment, fourteen employees sent a letter to the Pittsburgh Post in protest.

The last incident of note involved the theft of lead from the military facility. Eight boys and men employed at the Allegheny Arsenal stole varying quantities of lead; then delivered them to a Lawrenceville widow named Margaret O'Connor, who melted the metal and cast into bars. In turn, the lead was then delivered to a man who resided in the Diamond. A total of ten arrests were made in the case.

The American Civil War was the heyday of the Allegheny Arsenal. A few years thereafter manufacturing at the military facility ceased. While there were other incidents that resurrected interest in the old Arsenal prior to being abandoned by the United States government in 1926, none exerted such a profound influence on the history of the institution as the period between 1860 and 1865.

For more information relating to the Arsenal, read: Pittsburgh's Forgotten Allegheny Arsenal by Jim Wudarczyk. The book is available from Closson Press, www.clossonpress.com; and the Lawrenceville Historical Society lhs15201.org